This excerpt is taken from a chapter titled “Habits of Will” in John Dewey’s 1921 Book Human Nature and Conduct

“Recently a friend remarked to me that there was one superstition current among even cultivated persons. They suppose that if one is told what to do, if the right end is pointed out to them, all that is required in order to bring about the right act is will or wish on the part of the one who is to act. He used an illustration, the matter of physical posture; the assumption is that if a man is told to stand up straight, all that is further needed is wish and effort on his part, and the deed is done. He pointed out that this belief is on a par with primitive magic in its neglect of attention to the means which are involved in reaching an end.

“A man who has a bad habitual posture tells himself, or is told, to stand up straight. If he is interested and responds, he braces himself, goes through certain movements, and it is assumed that the desired result is substantially attained; and that the position is retained at least as long as the man keeps the idea or order in mind. Consider the assumptions which are here made. It is implied that the means or effective conditions of the realization of a purpose exist independently of established habit and even that they may be set in motion in opposition to habit. It is assumed that means are there, so that the failure to stand erect is wholly a matter of failure of purpose and desire. It needs paralysis or a broken leg or some other equally gross phenomenon to make us appreciate the importance of objective conditions.

“Now in fact a man who can stand properly does so, and only a man who can does. In the former case, fiats of will are unnecessary, and in the latter useless. A man who does not stand properly forms a habit of standing improperly, a positive, forceful habit. The common implication that his mistake is merely negative, that he is simply failing to do the right thing, and that the failure can be made good by an order of will is absurd. One might just as well suppose that the man who is a slave of whiskey-drinking is merely one who fails to drink water. Conditions have been formed for producing a bad result, and the bad result will occur as long as those conditions exist. They can no more be dismissed by a direct effort of will than the conditions which create drought can be dispelled by whistling for wind. It is as reasonable to expect a fire to go out when it is ordered to stop burning as to suppose that a man can stand straight in consequence of a direct action of thought and desire. The fire can be put out only by changing objective conditions; it is the same with rectification of bad posture.

“Of course, something happens when a man acts upon his idea of standing straight. For a little while, he stands differently, but only a different kind of badly. He then takes the unaccustomed feeling which accompanies his unusual stance as evidence that he is now standing straight. But there are many ways of standing badly, and he has simply shifted his usual way to a compensatory bad way at some opposite extreme.”

***

John Dewey was an American philosopher, educator and psychologist. He was the founder of the school of philosophy known as pragmatism, and his ideas had a profound impact on American education.

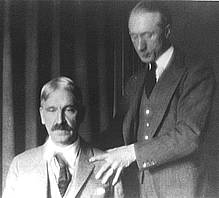

The “friend” mentioned in the first paragraph was F. M. Alexander. Dewey wrote the introductions to three books written by F. M. Alexander and was a great supporter of Alexander’s work – now commonly called the Alexander Technique.